View the collection here

Ciao, Italia

‘Four years passed and so I took an overdue trip to visit my father, originally from St John’s Wood, London, who, now in his late 70s, resides in a 1950s converted farmhouse in the region of Abruzzo, Italy. The inspiration that guided this solo trip to Italy came after looking through a photo book of mine ‘In Veneto, 1984-89’ by photographer Guido Guidi.

After spending a couple of days in the countryside, overlooking the foot of the Apennine mountain range, drinking espresso and sampling the local food, I planned to head south, towards the west coast of the Italian peninsula, in the direction of Naples. A few days before setting off, news broke that an area of the city was struck by the strongest earthquake in 40 years, with fears of a volcanic eruption from its neighbouring volcano, Mount Vesuvius.

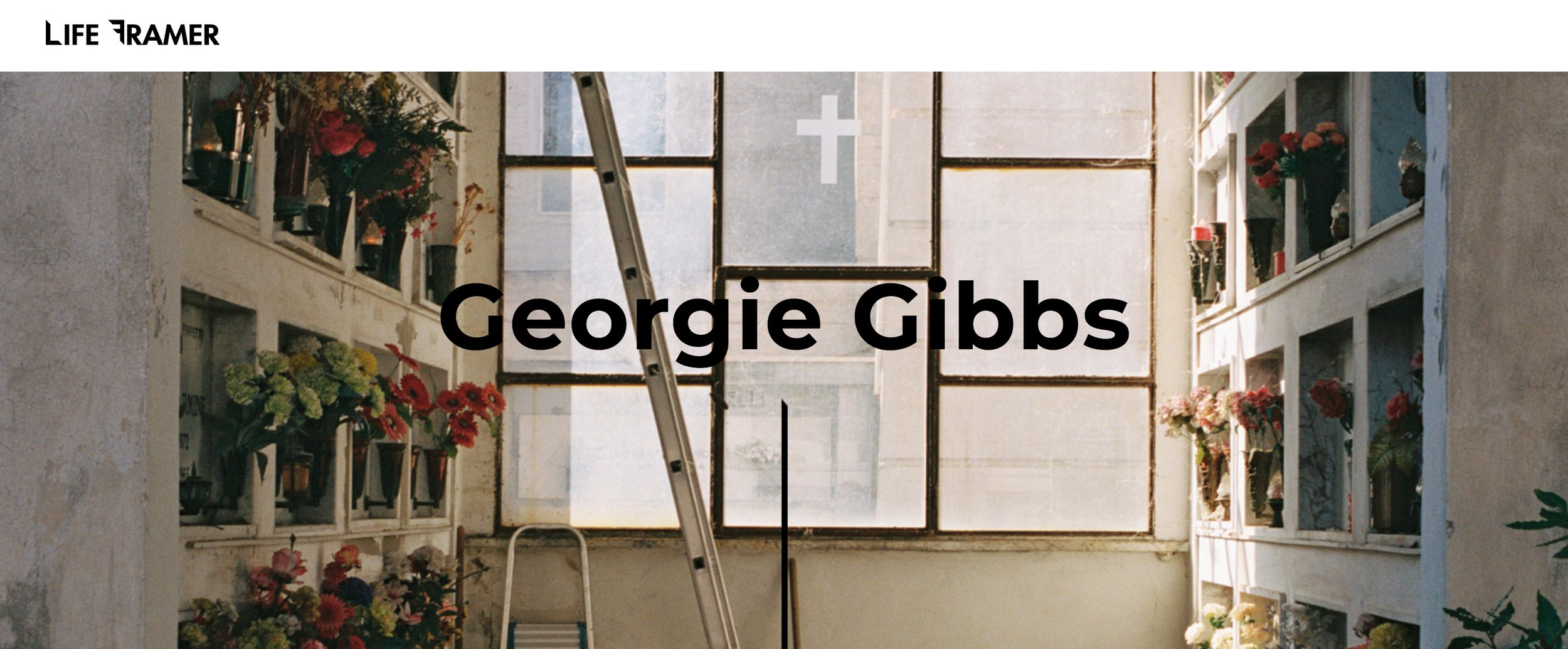

During the trip, an article by The Guardian caught my eye, about one of Naples's cemeteries, with the headline “At least a dozen coffins have been left dangling in the air after the collapse of a four-storey building containing burial niches at the oldest cemetery in Naples”. It was then that I discovered Italy’s hauntingly beautiful cemetery of Poggioreale (also known as Camposanto Nuovo).

“Poggioreale” which translates to “royal hill” is one of the largest cemeteries in Europe. Its maze-like network is spread across a hilltop overlooking the city. Opened in 1837, after an area near the church was becoming overcrowded with graves, many families built private crypts and chapels which were built to “aid the soul's passage to heaven”.

Vendors selling flowers are stationed at all entrances. What drew me to visit there were the ornate marble structures, and flowers carefully tended to, that pay homage to those who have gone and the legacy that they’ve left behind. I found that the coexistence of the living and the deceased can in many ways be comforting, showing the connection between generations. A place where comfort and unease coincide. A place that bridges the gap between the past and the present, and where introspection and reflection connect with the eerie beauty of mortality.’